Part IV

“1:36:12,” yelled a race marshal. I wasn’t sure which of the six. The one writing with the pad and pencil? Probably the one kneeling down with the stopwatch. 1:36:12. A respectable half-marathon time. But slower than it felt.

In modern road races, runners wear an electronic chip — most frequently attached to the bib or, as in our case, laced through a sneaker. The chip serves two purposes: electronic interrogations at various checkpoints discourage potential course-cutters and start/finish-line triggers ensure accurate timing. With chip time, your clock begins when you cross the start line and ends when you cross the finish line. Before RFID technology gave us chip time, there was only gun time. With gun time, everyone’s clock starts simultaneously. Doesn’t matter if you’re toeing the start line, at the back of the corral or in the bathroom. Before chips, race marshals recorded finish times manually. With a stopwatch. And a pencil.

Gun-time still presides over podium position. Reverent runners reserve the front of the starting corral for the elites. That’s where Jackie lined-up. And Pak Chol-gwang (DPRK). And Ketema Bekele Negassa (Ethiopia). The starting gun fired at 9:30am. I was in the bathroom.

Run enough races and you will develop a pre-race routine. Incidents and accidents inspire peculiarities, but all address four foundational questions:

- what should I eat?

- when should I eat it?

- when do I go to bed?

- when do I wake up?

I optimize my routine for one goal: don’t use the bathroom mid-race. On paper, Saturday night’s and Sunday morning’s schedules would abide. Saturday dinner was early and Sunday morning provided time for the usual coffee, breakfast and three bathroom stops. The last of which always occurs at the race venue.

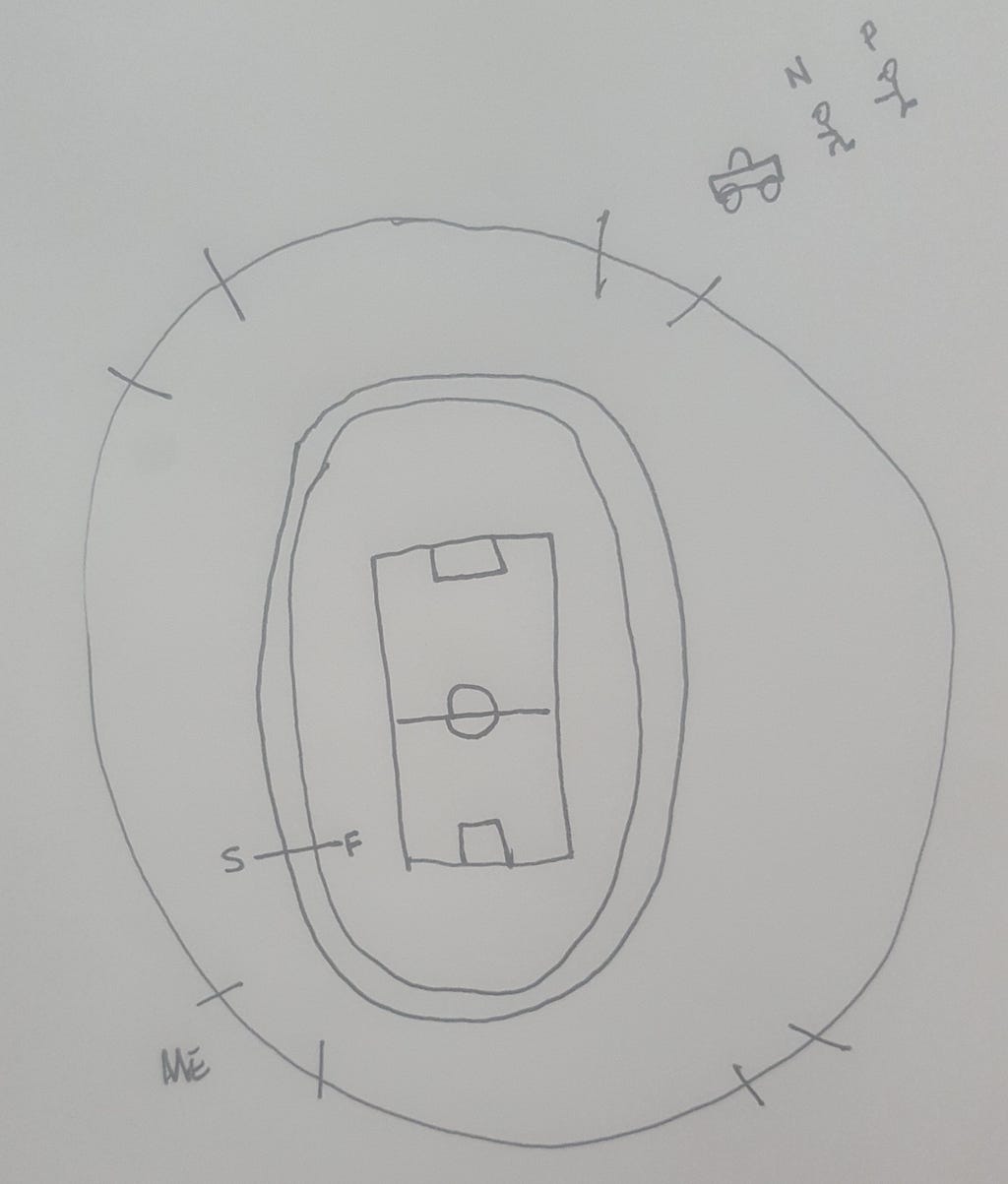

I located the stadium’s bathroom as soon as we arrived. The opening ceremony would end ten feet from its entrance. That would give me 15 minutes to use the bathroom and make it to the starting corral. Doable. Except the opening ceremony started late. When we returned to the tunnel there was a dash for the head. The 60 runners in front of me meant missing the gun. I was fine with this. We had chips.

Leaving the bathroom, I entered the tunnel to a stampede of 1,500 runners. As the back of the pack trickled from the track to the tunnel to the streets, my roommate Craig passed me. Gooooooo! Not to worry, Craig. We had chips. I made my way to the now deserted track: just me, a few other bathroom-first runners and 75,000 still-cheering fans. I was about to run the most glorious warm-up lap.

Running is basic. We learn to do it at an early age. We love to do it at an early age. There’s a popular theory we are born to run. Chances are you do not any more. Maybe you remember a time when you did. Even for a few seconds. It felt good. Like riding a bike accelerating down hill. Your eyes widen. Your focus sharpens. The wind, rushing over your ears, silences everything but the wind rushing over your ears. Nothing else exists. That’s a runner’s high. Runners chase it as much as any victory or personal record. That’s what we were after Sunday morning. A break from the hand-holding and the chaperoning. North Korea dictates every aspect of the tour: even the logo size on our running gear — 4cm x 4cm max. But they couldn’t fuck with running.

I crossed the start line and picked up the pace.

The miles flew by. I reigned myself in a few times to take measure of what was happening. I didn’t want to forget.

Running through the streets of Pyongyang felt like flying. We had the road to ourselves. We could cruise the middle or bank to the curbs for high fives until our hands hurt. I connected with the eyes of the elder North Koreans. Along with the children, they expressed unadulterated joy. The children screamed english “hellos”and ran along side us when their parents permitted. The elders merely gave a smile. But how powerful and pure. They knew. Everyone between hesitated, cautious of who might be watching from an overpass.

A week and five months have passed since the race. I recall isolation more than anything. My delayed start meant I’d run most of the course alone. By the start of the second 10k loop there wasn’t a runner in sight. Just long stretches of road so infrequently driven dust and dirt built in the middle. As the pollution fell from whatever coal refinery was closest, it tinted the blue sky a forlorn shade of yellow. To my left and right, sidewalk spectators served poor distraction from the desolation and dystopia behind them. This was more Mad Max than capital city.

The finish line appeared before I was ready. So soon? One final kick and I crossed. That’s when I heard it.

After catching my breath, I returned to the bus, changed clothes and found a seat inside the stadium. To keep the crowd entertained for two marathon hours, organizers scheduled a soccer match. It was still being contested when the pace car entered the stadium. Few noticed.

A marathon stretches 42,195 meters. The fastest a human has ever run that distance is 2:02:57. No one expected the record to fall that day in Pyongyang. The competitive international field was likely to finish around 2:10:00 — close to the course record.

Race organizers usually place clocks at water stations, distance markers and certainly finish lines. The only clock on the Mangyeongdae course was mobile, mounted to the top of a vintage Mercedes Benz. It kept ten meters ahead of the race leader, Negassa, as it entered the stadium and turned left on the track.

Once inside the stadium, the finish line measured 170 meters away. Negassa entered first, holding what seemed to be an insurmountable 25 meter lead on the second place runner, North Korea’s Pak. Tunnel behind him, Negassa followed the pace car now traveling clockwise on the track.

Maybe Negassa doesn’t train much on a track. Maybe he never led a race. Maybe he was hypnotized by the pace car. Maybe North Korea’s insanity got to him. But you don’t run clockwise on a track.

Before Negassa realized he was running the wrong way, Pak emerged from the tunnel. Two race marshals pointed him to the right. Where did they come from?

Negassa sensed something wrong halfway down the back stretch. Looking over his right shoulder he saw Pak running away from him. Negassa about-faced and launched into a sprint. The gap narrowed but never disappeared. Just past the finish line, exhausted, baffled and soon-to-be angry, Negassa bent at the waist. Head down and hands on his knees he was in perfect position to see the race marshal’s hand grabbing for his laces. With a grip, he began to drag Negassa’s foot towards the finish line. The rest of Negassa reluctantly hopped in tow. Close enough, the marshal slammed Negassa’s foot on the finish line. Maybe the chip registered then.

On April 28th, exactly two weeks after the race, our tour company via email relayed a message from our hosts:

Apologies for the delay in sending this out to you, it has finally been received from Pyongyang now. Attached please find the final list of times and places from our Korean partners in this year’s marathon. Sadly some of you may have not had a time listed on your certificate, I’m afraid if this is the case then you likely also won’t be on this list — the Koreans have told us that some of the chips were not laid horizontally on the running shoe (some may have placed it inside the shoe), others didn’t run across the starting carpet at the beginning of the race, or leapt over the finishing carpet so their time wasn’t recorded. We’re very sorry that in these cases no time was recorded, apologies for any disappointment.

Fuck you, North Korea.

The DPRK has been making news lately: nuclear tests, vlogger propaganda and sarcasm banishment. One North Korea-related story you may not be familiar with is that of East Asia Tribune reporter Chu Jingyi. Jingyi visited North Korea undercover. Posing as a Chinese business executive looking to negotiate a large coal purchase, Jingyi secretly sought access to a rumored North Korean brothel.

Jingyi finds what he’s looking for. Returning to his hotel after a late night in the brothel with a beautiful woman, Sun-Young, Jingyi’s cover is discovered by his state issued tour guide — who turns out to be Sun-Young’s estranged father. The tour guide agrees to let Jingyi go on one condition: Jingyi must help free his daughter. Jingyi agrees. On a subsequent trip, Jingyi and the tour guide devise a plan and free Sun-Young from the brothel! They spend a few days in a Pyongyang safe house until it is clear for them to flee the country. On the train to China, a ticketing agent recognizes Jungyi. He leaves his readers a cliffhanger.

With Jingyi’s sixth and final installment yet to be published, the East Asia Tribune called a press conference. It had been weeks since anyone heard from Jingyi. EAT staff members and readers were becoming anxious; as worried for the well-being of Jingyi and Sun-Young as they were interested to hear how the story ends.

I was one of the enraptured readers. I returned to the site every day looking for the final chapter. I grew concerned for Jingyi and Sun-Young. I had been to North Korea. I know what getting out is like! So I was relieved to hear EAT’s news: Jingyi and Sun-Young were safe, but only after a Chinese border shoot-out with North Korean soldiers; Jingyi would publish the final installment when things settled down.

Three weeks later and still no conclusion, tragedy struck. EAT reported armed men in an unmarked van gunned down Jingyi and a pregnant lunch companion dining at a Kuala Lumpur cafe.

The news shocked me. I thought of Jingyi’s courage and Sun-Young’s enslavement. She only just tasted freedom. How tragic. I thought of their story and how they had made it so far against what had to be impossible odds. Even getting as far as they did was almost too good to be true.

Someone made it all up.

- pictures are not mine, clicking them takes you to the source

Also published on Medium.