Part III

30 seconds after introducing myself she was asking about my divorce. North Korean women move fast. Even state-minted tour guides. Han, or Ms. Han, as we were instructed to call her, was our substitute on Monday, the last day of the tour. She told me I looked Canadian. No, Mexican. “Anything but American, right Ms. Han?” I shouldn’t have said that. Please get my humor. Please get my humor. “Oh, that’s OK. We don’t mind Americans, just their government.” It was a week before tax day. “Me, too, Ms. Han.” She was sweet. And smiled a lot.

Every week 27 flights, 23 in winter, wrap on Pyongyang’s runway. It’s a long, lonely stretch of road littered with moth-balled Tupolevs on either side. On the taxi, which felt unnecessarily long, we had time to think. How old are these planes? What else is a bump away from breaking? How much flight time do the pilots of the world’s worst-rated airline get? Before we could seriously reconsider our option to fly home three days later, we stop just short of the gate. Another head scratcher. Ten minutes later we’re standing in the cavernous, newly renovated International Terminal waiting for passport and luggage inspections.

I’m nervous. Moreso for passport control than customs. Before leaving Seoul I decided to bring only clothes into North Korea; no media of any kind, nothing with an on/off switch, not even my running watch. GPS devices are contraband. I left a bag in Beijing with electronics and anything that had Korean writing on it, including my work-issued passport cover. I noticed the tiny Hangul characters on the back just before leaving the hotel. The customs examination should go fine. But, I filled out the North Korea arrival card with my US forwarding address and indicated my job was in Seoul. Probably not a big deal, but a thirteen time-zone commute could look suspicious.

“Annyeonghaseyo.” I handed the agent my passport and arrival documents. “You speak Korean!?” He responded in English. “Aniyo.” I disappointed him. He looked down at my passport then shifted his eyes up to me. Down at my passport. Shifty eyes back to me. A third time, just to make sure I know who’s boss. “You’ve lost a lot of weight.” Image is important here.

On to customs, which goes mostly as expected. An older official was interested in the french press-shaped impression the french press in my bag made on the x-ray machine. Only after smelling the grounds packed inside was he satisfied it was a indeed just a french press. Bad coffee followed Getting Detained on my North Korea risk list. I repacked my bag and entered the lobby, where I’d wait for the rest of my group.

The lot of us totaled 140. Our tour company broke us into seven groups of 20 for two reasons: our itinerary was packed with many small locations — restaurants and gift shops — and small groups simplified surveillance for our two North Korean hosts. Pyong, more experienced, sat at the front of the bus and provided in-transit commentary. Ms. Ri, on her first tour, studied silently from the back. Our hosts spent a lot of bus-time on their phones, mostly with each other.

After leaving the DPRK I learned Pyong claimed to be Otto Warmbier’s tour guide — an irrefutable claim any guide could make. Pyong told a lot of lies on the trip, but those were scripted. Through one-to-one casual conversations and karaoke duets — My Heart Will Go On, his choice — I got to know Pyong as a well-intentioned, honest guy. I believe him. Had I learned sooner of his celebrity status I would have spent less time trying to crack Ms. Ri’s toothy grin.

“Ms. Ri, are you having fun!?”

“Fun? What is this word?”

I strongly suspect Otto Warmbier guilty of being a bro. Pyong could have confirmed it. Now I’ll have to wait.

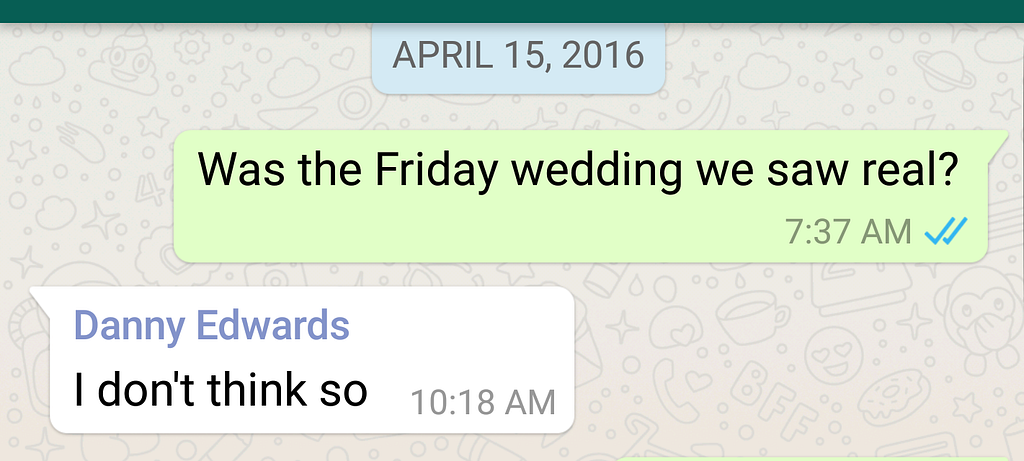

The Friday night bus ride from the pristine international terminal through rush-hour Pyongyang, flush with brand new apartment buildings and bustling with activity, gives me pause. Is this the same unemployed, starving and destitute Pyongyang I read about? As the sun begins to set we stop in Fountain Square. Pyong tells us it’s a popular place for weddings. It’s beautiful. We stroll the grounds and happen across newlyweds taking pictures. They ask us to join them. Of course!

The tour spans four days and three nights: Friday afternoon arrival in Pyongyang; Friday night sightseeing; Saturday sightseeing; Sunday morning race; Sunday afternoon sightseeing; Monday morning sightseeing; Monday afternoon depart Pyongyang. The days start early and end late, e.g. Saturday sightseeing started at 8:00 and ended at 20:30, with the option to see North Korea’s first “girl power” movie, Comrade Kim Goes Flying.

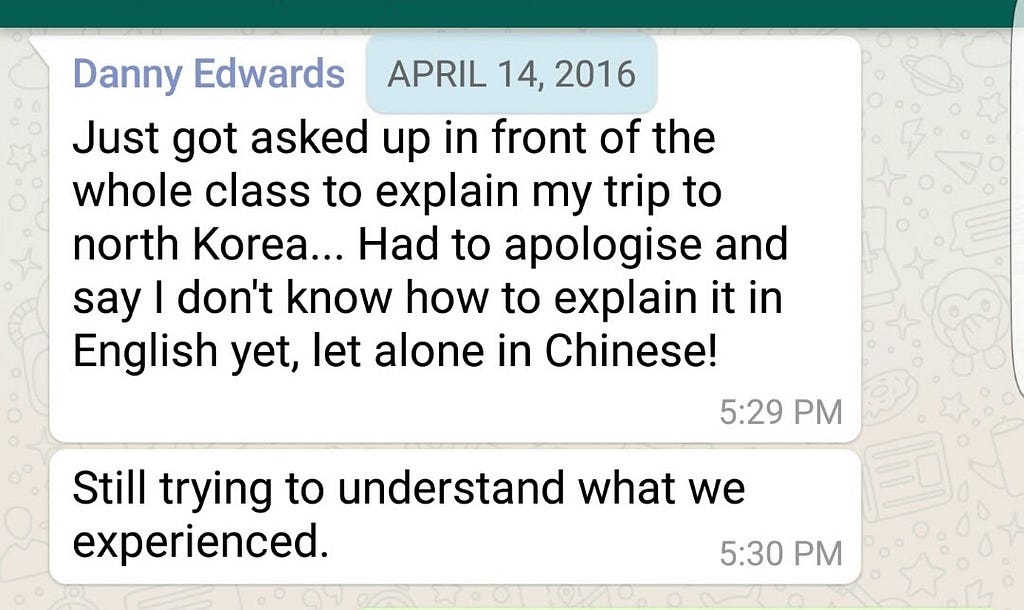

The Korea International Travel Company, the North Korean organization responsible for tour logistics, deliberately stuffs the itinerary. Down time could be filled with critical thinking. The near-frenetic pace is exhausting. As with most trips, you don’t fully appreciate them until after you’ve left. North Korea is the same but worse. After more than two weeks of reflection I, like Danny, am still not sure what I saw. I’m 99% positive it was all a lie. I’d be 100% if I never went. But propaganda works.

Pyongyang is a movie. You start the trip as Truman Burbank and end it as Neo. Repeated wholesome coincidence gives way to skepticism and doubt. At some point, Saturday night for me, you take the red pill and wake up. First you see the glitches. Then you see the matrix.

The sidewalk scene on Friday at 17:00 is the same as Saturday 8:00 and later that night at 22:00. People are dressed the same, carrying the same brief cases, walking with the same I’m-late-for-my-meeting focus. What meeting? No one’s going into or coming out of the salons, grocery stores, and bowling alleys. The water park is empty on a Saturday. Not even a ripple in the wave pool. No one’s having date night. No one lives in the apartments. So who put the fresh flowers on the balconies? No North Koreans in the gift shops or the restaurants we visit.

My a-ha moment came in the subway. A North Korean girl, wearing pink, walked the length of platform and stopped in the middle of our group. She boarded and sat with us, still as absorbed in her tablet’s screen as when I saw her descending the escalator. Pink, tablet, solo female silently mixing with foreigners.

No.

And now you know. And now you know they know. And now you know they know you know. And you want them to tell you they know. Because you’re going crazy seeking that last 1%. I think it’s called closure. Murmurs on the bus turn into probing questions of your guides — but nothing that gives you away. “Did North Korea have allies in the War?” You know the answer is, “the only reason we exist today is because China gave us 300,000 soldiers.” They know this. But they can’t tell you or they’d be sent to a gulag for the rest of their lives. So, they give you a prepared answer. And hearing that is like eating Cheetos. Empty calories. And this is how it goes for the entire trip. And the logical part of your brain starts to side with them. Because keeping up an illogical charade isn’t logical. What warped system of government takes the time and money required to create a 400 square mile, 2.6MM person movie set with actors who pretend to have real jobs and talk on real phones and eat real food instead of actually giving them real jobs and real phones and real food? How far does this rabbit hole go!?

You don’t talk about this at dinner.

You drink beer and enjoy getting to know your fellow travelers. The conversation stays light. And ultimately turns towards Sunday’s race. This trip is about the marathon. With one exception I knew of, all tourists planned to run Sunday. But these weren’t runners.

Also published on Medium.